The India-China standoff which took place in Eastern Ladakh on 15 June 2020, has been labelled by some as “unprecedented”, largely due to the high number of casualties of Indian soldiers in the Galwan valley, even though the two countries fought a war in 1962 and were involved in a bloody conflict in 1967.

Another confrontation took place between the two Asian giants in the summer of 1986, almost 36 years ago on the other side of the Line if Actual Control (LAC). The standoff has many similarities with the current tensions between the two countries.

It was June of that year and New Delhi was caught in a sweltering summer when the temperature in the capital’s policy-making circles went up several notches — the result of the heat being felt high up in the Himalayas. On the morning of 14 June 1986, a patrol party of the Indian Army’s 12 Assam Regiment spotted a Chinese post and a few structures right near the Thandrong pasture on the banks of the Sumdorong Chu rivulet in Tawang district of Arunachal Pradesh. Alarms bells immediately went off and the information quickly climbed the rungs of the army.

The patrol informed its divisional headquarters, which then relayed the news to Fort William in Kolkata (then Calcutta), the headquarters of the Eastern Command. By the time the news could reach the Ministry of Defence as well as the Ministry of External Affairs on 16 June 1986. The classified note from the Assam Regiment also mentioned the presence of 40-odd People’s Liberation Army (PLA) soldiers in the area. Some Indian media reports, however, had anticipated the number to be 200. The development shattered a long-held assumption in New Delhi that the land on the banks of the Sumdorong Chu rivulet belonged to India.

Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi-led Congress government set out to resolve the issue. Within 10-12 days of the alert from the Assam Regiment soldiers, the government lodged an official protest with the Chinese. It even summoned the then Chinese Ambassador to India, Li Lianqing, and handed over a diplomatic note. Amid the diplomatic haggling, Beijing increased its troop presence rapidly to over 200 soldiers and by August, had even built a helipad and a few permanent structures there.

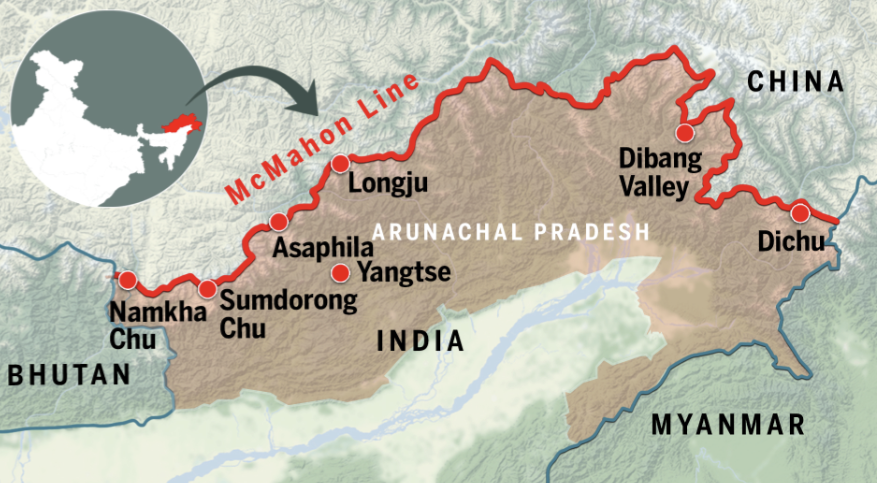

The two sides also set out to control the narrative, with the Chinese denying New Delhi’s allegations of an intrusion, and adopting the tone they did in 1962 — a Xinhua report of 1986, made available by the US government, quotes the Chinese complaining that it was India that was “nibbling at and expanding into Chinese territory”, adding that the McMahon Line was “illegal, null and void”. The Chinese media set out its own agenda claiming that it was India that had first built a “seasonal” post there n 1984, which they noticed and destroyed in 1986. They called it ‘Sangduoluo He’ in Chinese.

The Indian government quietly worked the channels and made the first offer of a truce in July that year — offering to not patrol the area that the Chinese have occupied if they pulled back. It was turned down. Instead, the conflict took nine years to be resolved.

The nine years saw a whole set of ups and downs and a series of diplomatic wrangling with a defiant Indian general keen on teaching the Chinese a lesson while a Prime Minister had his faith etched in the art of diplomacy. and a country, having tasted defeat once, determined not to be cowed into ceding any more territory.

But far more significant is the fact that in those nine years, when Indian and Chinese troops were eyeball to eyeball, not a single shot was fired, nor a drop of blood spilt along the then contested Tawang region.